This piece was written by Holland, and introduces the Three James's - in their day a cartooning force to be reckoned with.

Students and art historians researching cultural and political movements of the Thirties must encounter evidence of anti-war and anti-fascist activities as the Artists International Association and Left Review and so may find references to the Three James’s. Neither an acrobatic trio nor a musical group, they were three young artists who had decided, in that ominous decade, to devote what skills and time they had to supporting graphically and in unequivocal terms the broad front of the Left. Impatient of the mild posture of artists who were prepared only to be represented by typical gallery pieces to demonstrate their condemnation of war and reaction, they felt that desperate situations demanded unmistakeable exposure. The pen and the brush needed to b a great deal more outspoken if they were to have any effect.

These were not the only artists or creative workers to be active in this situation; their special contribution was that they were near enough in age, and that they shared conviction, skill and opportunities which while not identical, were close enough to align them on the same targets. They were artists by training and intention, graphic designers by occupation, illustrators and cartoonists by conviction.

Young artists, illustrators and designers, looking toward a newer broader public turned to print making techniques, particularly lithography. So James Boswell and James Holland joined the evening lithography class at the Central School of Art in Southampton Row, which was tutored by James Fitton, an outstandingly gifted draughtsman and painter from Oldham. There they met Pearl Binder, Lynton Lamb and others who found this medium responsive and not unnecessarily precious. So enthusiastically did they exploit these qualities, working on stone rather than plates, that newcomers had few opportunities to get their work put through the press by those excellent printers, the Devenish père et fils.

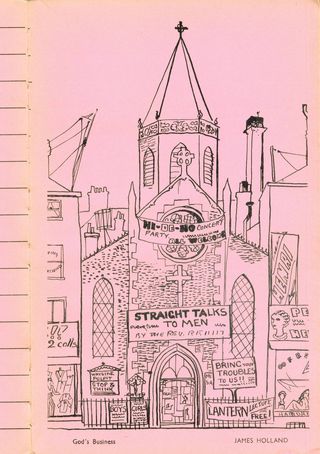

The evening classes became an available outlet for their anti-war and anti-fascist sentiments. As a consequence, Boswell, Fitton and Holland were asked to produce a pamphlet “It’s up to us”, providing visual impact for statistics and quotations emphasizing the dangers of the blindness of the government of the day to what was happening overseas and at home. This was a very successful effort and is still a most effective piece of visual propaganda, though very few copies can be in existence[1]. It lead to “the Three James’s” being in growing demand for many other assignments.

The Three James’s backgrounds were widely different. Fitton was a few years the oldest. The son of a Lancashire trade union leader, he had met at his Oldham home many of the stalwarts of the first Labour government, and his origins were Labour rather than Socialist. Very much a Lancashire lad, he was intensely ambitious and in pursuit of fame more than fortune, he came to London where his outstanding graphic skills found him a place in advertising. Intelligent rather than intellectual, Fitton was never swept away by political theorising from the extreme Left. The conservatism of the British working class was an attitude he well understood.

Boswell’s background could hardly have been more different. The son of a New Zealand schoolmaster he had been brought up in a small town in the North Island and received his education and art training in Auckland. Strong and solidly built, a rugger player and powerful swimmer, he found London had its disappointments and frustrations and the English often effete, and he cast himself in the role of the wild colonial boy. He was a man of bold gestures and disliked finessing in any form.

James Holland’s background had more in common with that of Fitton. Born in Kent, his father was employed by the Admiralty in Chatham dockyard and elsewhere, and he grew up in the Medway towns and a London suburb. He won scholarships to the Royal College of Art and in his second year there met Boswell.

In recalling the late Thirties, it is difficult today to be entirely objective and to dismiss hindsight. So much political naivety, so much disinterested idealism was in evidence, sometimes to be diverted and disillusioned before it could be converted into effective action.

The two developments in the increasing campaign against fascism and war brought their lithographs and drawings into a widening audience. The Artists International Association was founded and the monthly Left Review was published. In the early days of the AIA, their work when exhibited was perhaps noticed as being more professionally competent than the politically motivated but less technically assured efforts of many of the earlier members, but as the Association expanded, became less doctrinaire in pursuit of a united front among artists, so their contributions took on an aggressive posture. Boswell was the most committed of the three and became and active though not uncritical Party member. Fitton and Holland with more direct experience of working class life and ideals remained what would not be considered left wing Labour, with some belief in the effectiveness of a broad front of Left inclined organisations. They were of course extremely naive in the light of what we have since come to know of the alignments of that inter-war period. Many illusions have since been exposed, many causes betrayed, but no post-war criticism is acceptable that does not understand the threat that lay over Europe, that grew more menacing week by week and beyond the capacity and courage of the West to resist.

Left Review was a regular outlet for their cartoons and illustrations and a recent critic and historian has suggested that it was the Three James’s contributions that readers turned to most appreciatively, thought whether this was true of the dedicated Marxists is doubtful. A frequent criticism from this quarter was that too often they portrayed the working classes as downtrodden, victims of an inhuman system, hopeless and too down-and-out to resist exploitation. From a political, an Agitprop angle this was true, but where to find evidence of proletarian militancy? Boswell, the most politically committed, took this criticism seriously and many of the lithographs he produced at this period included heroic lorry drivers as vast and square as their own vehicles, defying the forces of reaction, marching against Fascism with miners and dockers. But he did not forget the less heroic aspects of working class life in the back streets of Kentish Town, the cafes and amusement arcades of the North London inner and decaying suburbs. Having taken a job in a design studio in the City, he found a new field for satire in City tycoons and their Tatler-featured horsey women became his prey.

The role of the cartoonist, the graphical artist, is a curious one. It is almost entirely critically destructive, whether mildly and well-tempered or bitterly and savagely. If crisis and tension are the atmosphere in which the political cartoon flourishes or can be effective, then much of its function can disappear when as a result such tensions conflict.

To revert to the mid Thirties, certain writers and artists had founded an outlet for their work, including re-appraisals of existing standards, in Left Review, edited by Edgell Rickword. Many of the contents of Left Review, not least its cartoons, now appear naive; the capitalist still wore a top hat and watch chain and smoked a fat cigar, and Colonel Blimp typified the Establishment. But the re-alignment of total war involved the whole community and issues were no longer demonstrable in such simple terms of black and white. In the circumstances graphic comment needed to be more subtle, less explicit.

If Left Review had any sort of successor in the graphic field it was perhaps Lilliput which appeared in the happy and prolific period after the War until its premature demise with its stable companions Picture Post and Leader magazines.

[1] Tate Galleries Archive has one