Today's piece was written by Holland when reflecting on his childhood and a part of Kent that played a significant part in his life. The text is incomplete, and when (or if) we find the remaining section, it will be added as Part 2.

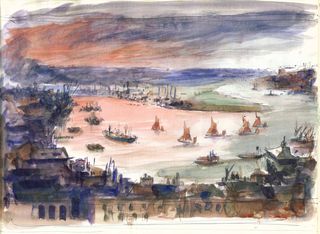

CHATHAM DOCKYARD RECALLED

The closure of the Royal Dockyard at Chatham attracted the attention of many whose previous acquaintance with that establishment must have been of the slightest, bringing forth as it did, stories of “dockers standing in tears at the final ceremony.”

There were of course, no “dockers” as such at Chatham or the other Royal Dockyards. The dockers’ function is to moor, load and unload cargo-carrying vessels. The ships of the Royal Navy were seldom concerned with cargoes, and their large crews could handle all the docking and loading requirements. The dockyard’s role was to build, and more importantly perhaps to maintain and repair warships of all types. The men who did this - generally known to the Navy as dockyard maties, included shipwrights, smiths, boilermakers, riveters, joiners and carpenters, patternmakers, riggers, electricians - all the army of skilled men needed to construct and keep a warship in service condition. White collar workers as well as labourers were also employed; there were also sail making and flag lofts in the yards. Naval and marine barracks adjoined the dockyards, which were the home depots of all RN ships.

Chatham had been the nearest dockyard to London since the sixteenth century, though there had been various lesser establishments on the Thames at Deptford and Woolwich. The road that led from the dockyard gate to London went through an area of Chatham known as The Brook, notorious for many dens and brothels where sailors, pay in their pockets and en route for the capital, could expect to be robbed , or worse. As late as the mid 1920s this welcome for Jack Ashore was in evidence, and one read in the local police court news of police raids on disorderly houses of elderly dames being sent to jail again and again for brothel-keeping in The Brook.

Sailors, marines and soldiers were a transient population. The permanent residents were the dockyard men. They lived in Chatham, in Old Brompton, some in Rochester and Strood, but by far the greatest number in New Brompton and Gillingham, and the similarity of much of that district to a Midland or Northern industrial town was due to dockyard workers many of whom had come from the North. A network of tramways covered the Medway towns and carried the men to the Yard, which started work at 7 o’clock or earlier. Open topped trams loaded with workers converged on the Main Gate, a rather impressive brick castellated structure still to be seen. Under the eyes of the Dockyard Police, the men streamed through to their workshops. At frequent intervals one would be stopped a random and frisked for matches which were forbidden in the Yard. A naked gas jet burned under the entrance arch at which the homeward bound would light pipe or cigarette.

Chatham could handle “first class battleships” of the early years of the century up to 16 or 18,000 tons. I clearly remember being taken aboard H.M.S. Goliath in 1911 by a much-loved uncle who was a sergeant of marines and being hoisted into the muzzle of one of her 12 inch guns.

The larger warships which succeeded this period did not, probably could not, attempt the long and winding approach from the river mouth, and would lie in the estuary, off the satellite yard of Sheerness. Workers who were taken daily by picket boat to these ships were known as “time-in-lieu men”, since they could not return home for a mid-day meal and so returned from work an hour earlier than the regular men. The appearance of time-in-lieu men dispersing from the Yard was the signal to prepare for the homecoming of the workers in general.

The influence of the Dockyard affected all activities in the Medway towns and many families were wholly dependent on it for employment. My grandfathers had both worked in the Yard, and one had died in the Yard before my birth. My maternal grandmother found herself still young, but penniless and with a large family of small children. She went to work long hours in the Flag Loft, as later did her eldest daughter, who eventually was in charge of that department. Her only son also went to the Yard and two daughters married dockyard men. Another married a sailor and yet another a marine. My father and his brother grew up as apprentices, though both were eventually out-posted by the Admiralty.

When the Dockyard flourished, the towns flourished; when retrenchment was the order, towns, trade and everybody suffered.

The Royal Dockyards employed both skilled and unskilled labour. I do not know how the unskilled were recruited, but entry to the skilled ranks was by examination. Every year the local schools, elementary and secondary, ran their Dockyard Exam classes for boys of 13 or 14. On an appointed day the lads presented themselves to sit a written examination. The successful gained admission to the Dockyard School - the same pattern operated at Portsmouth and Devonport. According to their marks, the boys had the choice of which craft or trade they would enter. They became apprentices, spending their mornings in the School and the rest of the day at their trade in the workshops. As might be expected, the School concentrated on mathematical and technical subjects, technical drawing being well taught, but an excellent curriculum in more liberal studies was also maintained.

This admirable system, though important in the history of education, is little enough known, but those educationalists who do encounter it have been very impressed by the amalgamation of education and training, a system still to be improved on.

At the end of his seven-year apprenticeship, the by now skilled young man would be employed in the Yard and after a period of satisfactory service could become “established”, his job guaranteed and a pension assured at the conclusion of his working life.

The great days of Chatham as a dockyard and garrison town were perhaps the half-century before the outbreak of the 1914 - 18 war. We still had the world’s greatest navy, with a fleet in every sea to protect many foreign stations. Naval and military barracks were in full use; the Royal Engineers had vast barracks at New Brompton, at the centre of which a grand equestrian - if that is the right word - statue of Gordon of Khartoum mounted on a camel, replica of the original in the Sudan, faced the East. The tale was told of a high-ranking British diplomat, recalled from the Nile, asking his small son what he would like to see again before leaving for England. “Gordon” was the reply that rewarded the Empire builder. Hand in hand they gazed at the statue. As they turned away the boy enquired “Who is that man sitting on Gordon?”

Sunday morning was a great weekly occasion, with marines, royal engineers and at times Scottish regiments marching to Church Parade at the Garrison Church, bands playing, brass bound white helmets flashing, bagpipes wailing.

War was the testing time. The dockyard was never busier, working day and night. Every day ships were being sunk by mine or torpedo, and every time a Chatham based warship went, down, more blinds were kept drawn in the little terrace houses of Chatham and Gillingham. But endless work brought relative prosperity to dockyard workers and the local tradesmen.

With the ending of the Great War, the workforce at the Yard was drastically cut, and men employed at levels of responsibility suddenly found themselves demoted, back at the workbench and lucky to be there. Ships that had been built in great numbers during the war years, heavy and light cruisers, above all destroyers, lay in long lines in the lower Medway, a permanent review of the obsolete, until they were one by one towed away to the breakers yards of the North.

These were lean years for the dockyard towns. But not only had these southern towns; the industrial North and the north Midlands no longer needed the work forces for wartime production. Unemployed workers and ex-servicemen, with no hope of a hometown job, headed south in search of work, renewing a traditional migration. During the periodical slumps of the last century, when development outran demand, mechanics and industrial workers trudged from the North, from the Black Country and the Midlands, to the supposedly prosperous South. Many of the workers at Chatham were probably children of these earlier migrations rather than offspring of Kentish peasants.

With my parents I had returned from London to Gillingham as part of the post-war retrenchment. We had found a house between the railway station and the ground of Gillingham football club, in those days remarkable only for the tenacity with which every season it applied for re-admission to the Third or Fourth Division. Down this Via Dolorosa a slow and sad procession crept daily, a mendicant procession of tuneless singing men in ex-army trousers and boots, some accompanied by wife and small children, turning as they slowly walked to scan the empty windows of the little terrace houses.

There was at this period a spate of lugubrious songs that could have been written especially for these despairing minstrels. “City of Laughter, city of tears, what are the secrets you hold ... hearts that seem bright will be breaking tonight in the City of Laughter and Tears.” “Just the tears of an old Irish mother”, “Smile awhile you bid me sad adieu”. There were rather more cynical, sophisticated ditties to be heard at the time, but not in the streets, “When you’re all dressed up and no place to go”, “Ain’t we got fun” and the abject “Buddy won’t you spare a dime?”

The unemployed singers were interspersed with other processions. The local cemetery lay on this route. You could travel from the station to a League match or your eternal relegation or promotion. During the years immediately following the War various epidemics took their toll, Spanish Flu in particular claiming many victims, aftermath of what was one of the most squalid wars in history. Several times a day the sounds of a military or naval band, playing the Dead March, would precede the passing of a procession drawing the flag-covered coffin on a gun carriage, followed by a firing party of the dead man’s messmates. Within the hour the procession would return at a brisk pace, the band merrily playing “The Girl I left behind me”, or some other more or less appropriate air, on the return to barracks or ship.

The Dockyard and the towns became increasingly an environment from which escape was to be sought. At intervals of several years, the Admiralty held examinations among the Royal Dockyards to prepare lists of men who might be offered promotion either at home or at one of the many naval dockyards overseas as jobs fell vacant. Gibraltar, Malta, Singapore, Hong Kong, Bermuda were among the station overseas. My father always sat these exams, came out near top, and then steadfastly declined any overseas posting, to my great disappointment, and so was passed over until the next examination was held. Eventually came an offer in the South Coast area, and our proximity to the dockyard came to an end.

My last encounter with the Yard was during the 1939 War. It was my assignment in the Ministry of Information to design a travelling exhibition to show the work of the destroyers in wartime.

[This story will be continued when we find the rest of the manuscript.]